Grappling and Gunfighting (A SWAT Cop Argues for Jiu-Jitsu)

By: Greg Lapin

(Originally published in Tactics and Preparedness Magazine in May 2019)

For the last 20 or so years I have made it my duty to ensure that I was as versatile in lethal skill sets as I could be. I began my martial arts journey at about the age of 19. I started in Kenpo and Jeet Kun Do. I rather quickly learned that either the style or the gym wasn’t for me as I didn’t see much use in kata, and the sparring was, in my opinion, less than realistic.

I then studied Muy Thai. Kicks, elbows, knees made sense to me. I went to Thailand and trained there for a couple of months. I got to kick the little bamboo that the five to seven-year-olds were kicking, which was as humbling as it was painful. Then, in 2006, I dove into Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. I am a fan of most martial arts and think that, without the watered-down commercialization of some of them, and within the original fighting roots of them, they all have useful aspects.

I do have my own opinion about what skills should take priority, though. From the time you learn to walk, you understand hitting. I don’t think there’s a parent out there who hasn’t had their kid get in trouble in nursery school for hitting another kid. Anyone reading this right now, if you’ve never had formal training on striking, whether it be boxing, Muy Thai or any of the other striking based martial arts; if I walked up to you and grabbed you by the throat, you would most likely push me or punch me away from you. And, most likely, it would be pretty successful, at least for the initial engagement. Now, take the same scenario, but I grab you with double underhooks or collar tie or—worse yet—the lapel of your jacket. If you have never had any grappling or wrestling training you are about to quickly get smashed on the ground, and if we are talking concrete and not a sprung, matted floor, one good throw or take down could likely end the engagement.

A good friend and a martial artist mentor of mine once told me, “All fighting arts are trained in theory, except for wrestling and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu.” (he was speaking grappling arts, so, yes, catch wrestling, Sambo, etc.) He went on to explain that with the striking arts you are hitting a bag or a pad of some sort. Even when you spar, most folks are sparring at about 50-60 percent with gloves, head gear, shin pads, etc. You are building skill, learning foot work, combos, technique and becoming a better striker—and I think that is important—but you are assuming that when you are hitting focus mitts that those strikes will be effective on your assailant. In my opinion, Krav Maga is the perfect example of this. It has some very effective techniques, which are lethal techniques taken from other, older, traditional martial arts, but when you see Krav practitioners working on their situational sparring and weapon grabs, they are pulling their strikes and moving at a fraction of the speed that real world encounters happen at. I understand that the training has to be conducted this way, otherwise there would be no members at your gym and your training partners would run out quickly.

I believe Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu (BJJ), hands down, should be what you train if you can only train one fighting style. I’m not trashing your style, but when I say BJJ should be the priority, I’m talking true, traditional BJJ that was originally for fighting, not the modern sport, pulling guard, butt scooting stuff seen in tournaments. Original BJJ had takedowns—Judo and wrestling-based throws. They used strikes and kicks to set up these takedowns and then they used superior body control to throw strikes or finish with a submission.

I have heard, “It would be a lot different if we could punch.” My answer to that is, “Yes, you would be bleeding a lot more before I put you to sleep.” Just because someone trains Jiu-Jitsu doesn’t mean that when it comes down to its’ application in the real world that they won’t throw strikes. I’ve used BJJ more in real world encounters as a police officer, SWAT assaulter, contractor, and the few outside of work encounters I’ve had than anything else. Guess what—I’ve very rarely ended up on the ground and certainly not on the bottom. Most encounters end with a violent takedown or throw, and in those that haven’t, I’ve been able to maintain a dominant top position while maintaining situational awareness and delivering strikes or escalating to a more lethal weapon if the situation required it. You won’t see me pulling guard and trying to arm bar or triangle someone on the street. I do agree that could be an easy way to get your head kicked in by one of your opponent’s accomplices.

Training in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu (and the grappling arts in general) will give you a skill set that is not innate. You will learn superior body control, the proper grips to use, both with clothes/gi and without/no gi. You will learn angles of attack and transitions when someone defends your initial attack. You will learn how to control another human and make them open themselves up for easier attacks, whether that be strikes or submissions and you will also learn–if you are taken down, overwhelmed and on the bottom–how to reverse that position or be just as effective from it.

“In the street, there are no rules.” True, but if you cannot control me or get your hands on me in a somewhat advantageous position, then you are going to have a hard time getting your finger in my eye socket or biting me. I’ve trained multiple martial arts and fighting styles, and I still wear the uniform of a police officer assigned to the SWAT team for a police department just outside New Orleans. Police officers must put their hands on people daily; more than any other armed profession in the world. I believe it should be a requirement by each state’s training council that police officers train BJJ and achieve at least their blue belt, (which, at a respectable school, should take about two years). Many cops don’t know how to put their hands on people constructively and are scared to engage. Without that confidence they sometimes turn to excessive force or unprofessionalism. They should be given the tools they need to protect themselves and do their jobs, and Jiu-Jitsu completes that tool set.

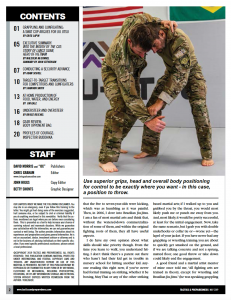

It is not much different for special operations units that focus on direct action missions. When they find themselves in a contact distance engagement during CQB, they need to be able to control unknowns and adversaries under varied rules of engagement. I was fortunate enough to attend the Special Operations Combatives Program’s (SOCP) Low Visibility Course while working for the U.S. Government. That course focuses mostly on standup grappling and Jiu-Jitsu, but stresses how to get on top and get up quickly, all while getting to a lethal force option. We say on the mats “Position before submission.” The same holds true in lethal encounters, “Position before you can access your lethal tools.”

I believe the proof is in the pudding and the mats don’t lie. Just because sometimes we are playing a “game” or “sport” doesn’t mean we don’t have the ability to dominate another person and then punch them or shoot them or gouge their eye out.

It doesn’t matter if you are a high-level black belt or a first day white belt. If you travel and visit another Jiu Jitsu gym anywhere in the world, you more often than not will be welcomed with open arms. Unfortunately, no martial art, fighting style or combatives course is going to make you effective over the course of a two-day class. These things take repetition and recency. You have to utilize the techniques under real pressure and full force sparring regularly to hone your skills. I recommend you find one that focuses mostly on self-defense-based Jiu-Jitsu and grappling, which includes stand up wrestling and Judo. If I had no choice other than to offer someone two days of training, I would focus on distance management and body control. More specifically, after two days I would make sure you understand underhooks and overhooks. I would make sure you could head fight and maintain dominant head control and positioning. I would also focus on grips both gi and no-gi which include wrist/sleeve control, inside bicep, lapel control and collar ties, as well as several others. We would cover a few very basic, high percentage take downs such as Osoto Gari, the simple but effective body-lock take down and possibly a hip toss. Once on the ground I would cover pressure and control from mount and one of my favorite positions, knee on belly. As we go on, I would teach a couple of high percentage means of reversing a bad position should you end up on the bottom. If you happened to get mounted, you need to understand how to protect yourself from eating punches by unbalancing your assailant with a big “Upa,” otherwise known as a bridge. You must learn the arm trap and roll out of mount to put you in a top position. You also must learn to manage the distance with guard, but to more specifically sweep your assailant to get on top or utilize your knee shields and up kicks to quickly get up using a technical stand up and combat base.

I didn’t once mention teaching any submissions. For the armed professional, the real magic of BJJ comes in the form of superior body control and managing distance. That is the reason we employ different tools or weapons. Distance management is the key in any fight. We have edged weapons, pistols, subguns, rifles, precision rifles, and A-10 Warthogs. It’s no different in the world of combatives. Learn how to control the distance and understand your weapons from each and you’ll be set up for success.

Swallow your pride, leave your ego in the car, find a good gym that suits your need, and go train. The hardest part is walking through the door. Someone smarter and tougher than me once said, “Jiu-Jitsu is for everyone, but after a few months it’s just for half of those people, and after a few years it’s just for a handful of rare savages.”